It feels like I’ve had Shenmue on my Steam Deck for years now. I bought it years ago — in fact, I’m pretty sure it was the first game I bought on Steam — but I just couldn’t get myself to hit the launch button.

Which is a weird thing, because Shenmue is my all-time favorite video game. I kept coming up with excuses as to why I shouldn’t replay it — the timing just wasn’t right, there was other stuff I needed to work on, I couldn’t handle the time investment, etc.

But over the fall, I did boot up the game. And as soon as Ryo let out that iconic “NOOOOOOO” following his father’s death in the game’s opening cutscene, I had the reaction I feared I would have.

I started crying.

And it happened again the first time I opened the sub-menu and heard that iconic “journal music.” And again when Ryo found that poor little orphaned kitten.

Playing the game for a mere two hours, I felt exhausted from crying. My face hurt, my eyes burned and I actually felt a little dehydrated. It took so much out of me emotionally, I wondered if I ever should’ve restarted the game in the first place.

Now, it’s not that Shenmue isn’t an emotionally moving game in its own right. Because it totally is. But the game alone wouldn’t cause me to fall apart that badly. In the back of my head, I already knew why replaying the game was such a taxing experience.

Because it was my mom’s favorite game.

I feel like I’m preaching to the choir whenever I exalt Shenmue. But you have to always assume there’s going to be someone out there who has never heard of the game before, so you have to wedge in a brief synopsis of the title somewhere.

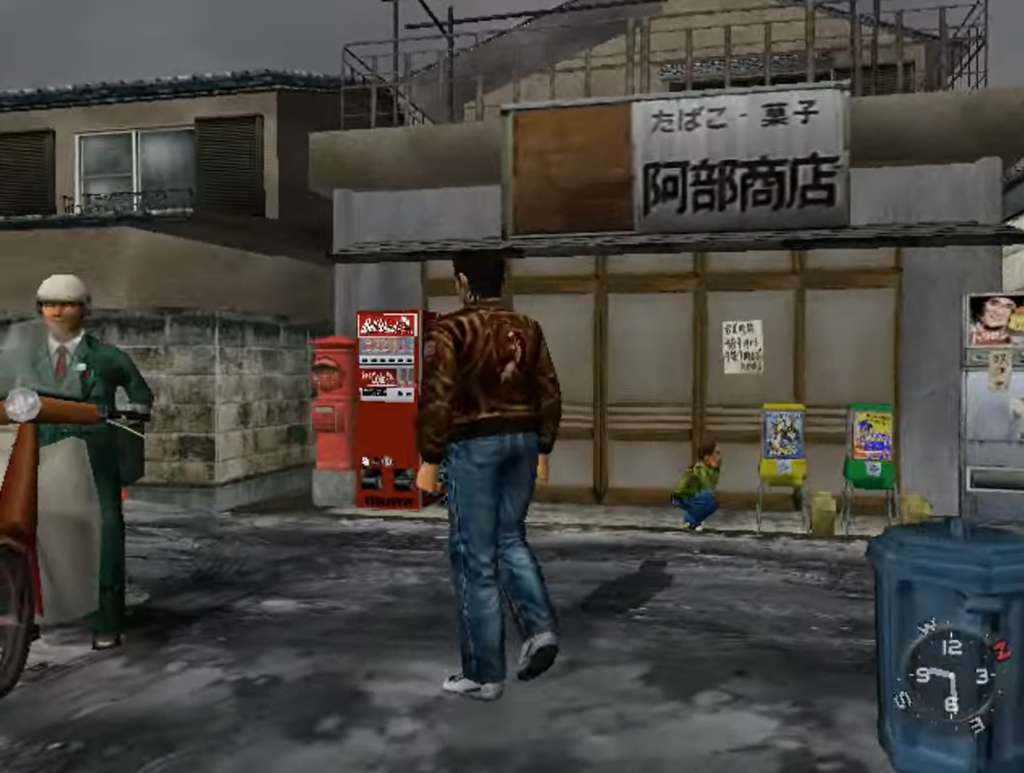

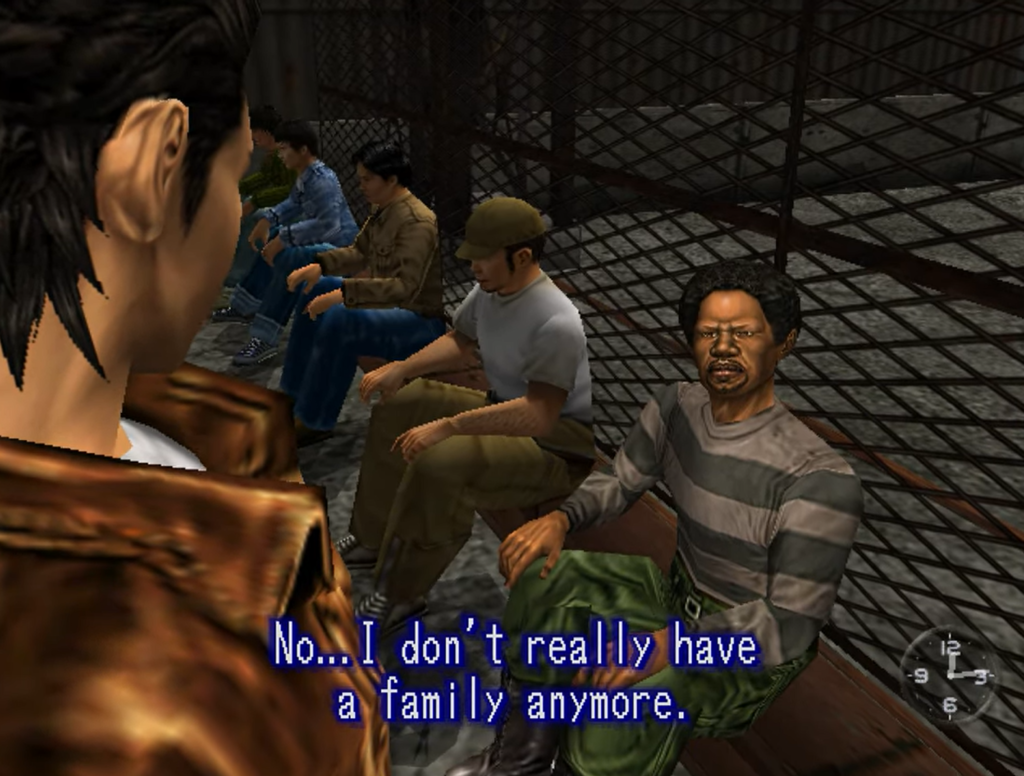

If you’ve never played it before, Shenmue is basically a coming-of-age story and a kung-fu revenge melodrama at the same time. It’s set in 1986 — oddly enough, the year I was born — and revolves around a teenager who has made avenging his father’s death his life’s calling. Being a video game, it also incorporates a lot of detective work — i.e., having to complete this random task in order to complete another random task in order to move the story forward, so on and so forth. What made Shenmue radically different from virtually everything else on the market in 2000 (when it was originally released in the U.S.) was its level of immersion. Long, long before games like Skyrim or The Witcher III, the Dreamcast killer app gave players a sprawling, living world to explore — complete with hundreds of people you could talk to, engage in fisticuffs or maybe even fall in love with.

The virtual Dobuita presented in Shenmue reminds me a lot of where I grew up. Indeed, some of the backgrounds and settings are so similar, it’s almost eerie. Walking around as Ryo in Shenmue felt a lot like walking around in my hometown. It was the first video game that actually made me feel like I was in a “real” environment and not just a bunch of random stuff cobbled together by a game designer. And I’m pretty sure it was the first video game I ever played that evoked real emotions inside me while I played it. This wasn’t Doom or Grand Theft Auto or Super Mario Bros. 3 — this was *literally* a movie that I controlled, and I couldn’t help but feel an instant kinship with Ryo.

Like a lot of your mothers, my mom HATED video games. She would always sit there in her recliner making fun of me for wasting so much time on stuff like Sonic 2 or Gran Turismo. She just didn’t see the appeal, and I didn’t think she ever would.

Then Shenmue happened.

One random afternoon she saw me playing it and I saw something different in her eyes. This wasn’t the normal disdain I saw when I played virtually every other video game. In fact, she looked a little … intrigued … by what was going on in the game.

I had to give her a quick primer on the story. She was perplexed at first. So here’s a game where you’re not in a spaceship, you don’t jump on Goomba heads and you don’t kill anybody? And it has something that resembles an actual, honest-to-goodness story?

She sat back down in her recliner. And she leaned forward. And she watched me play Shenmue for a solid hour.

The next afternoon when I got home from school, she called me into the living room.

“Before you start doing your homework,” she said, “I want to see what happens to that Japanese boy first.”

Yes, my mom never called it Shenmue. As far as she was concerned, the name of the game was “Japanese Boy,” and it wasn’t long before she was as obsessed with it as I was.

She couldn’t figure out the nuances of the Dreamcast controller, so she had to make do with watching me play it. So in a way, she was one of the first Twitch adapters, about a decade and a half before Twitch was even a thing.

Her running commentary on the game is wired into my skull. I can still hear her talking about “that one skank outside the bar” and egging me on during the fork lift races and how she was legitimately on the edge of her seat during the 70-man battle royal, almost like she was watching a Chuck Norris movie or something.

For a solid month or two, my mom was engrossed in the Shenmue experience. I’m not sure Yu Suzuki had 50-year-old women in the Deep South pegged as the target audience for the game, but she sure as heck liked it.

So fast forward a few years. I’ve upgraded to the O.G. Xbox and I’m playing Shenmue II in my bedroom. My mom walks in and says “hey, are you playing Japanese Boy again?”

I told her this was the sequel and she literally jumped for joy.

“They made a Japanese Boy II?” she said. “Turn that thing off, hook the machine into the big screen in the living room and start all over, I want to see what happens to him!”

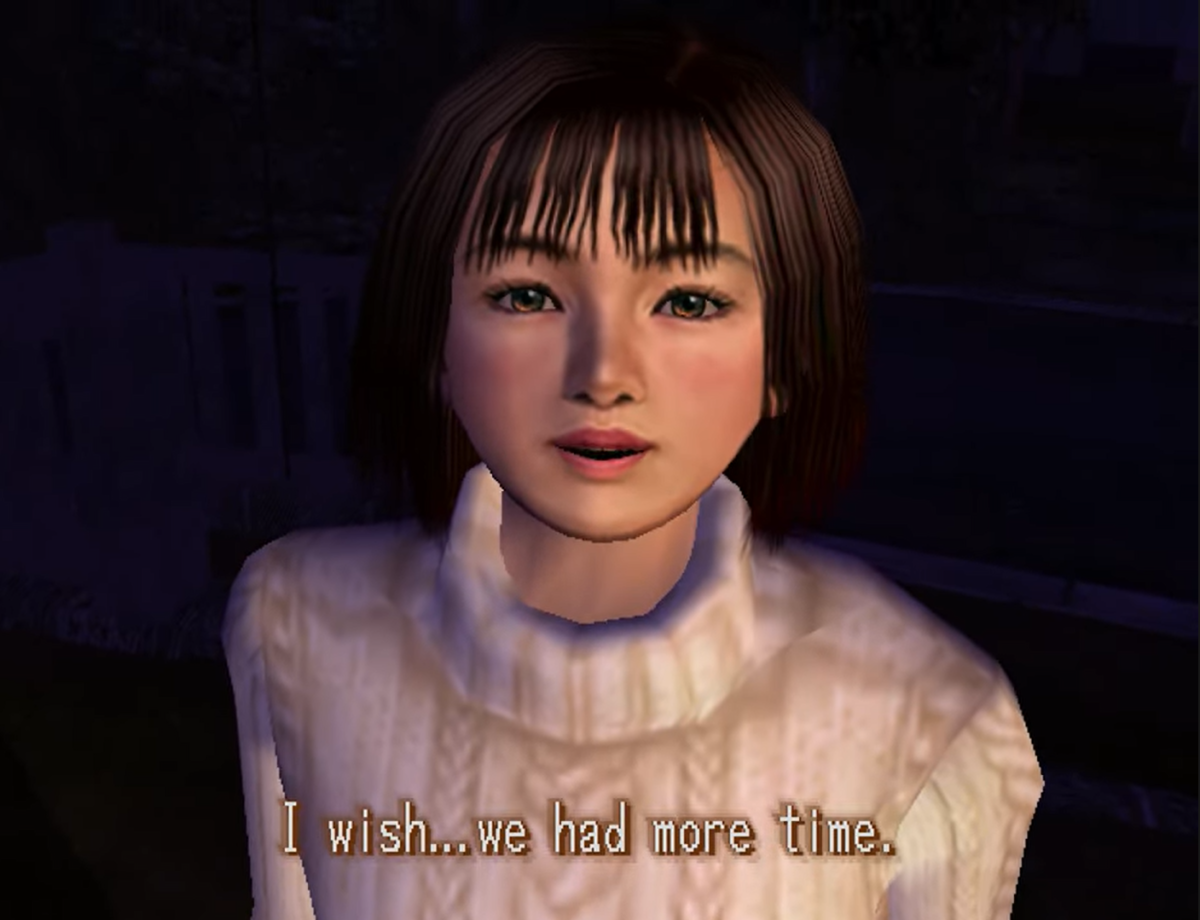

It took me an entire summer to beat Shenmue II. And my mom was there almost every step of the way. She had strong feelings about this one, as well — specifically, she couldn’t believe Ryo would abandon Nozomi for that “tramp on a bike,” and she would always laugh her head off during the mini-game were you had to help Delin move crates around. For years afterward, she would spout out an impression of “put it down, herrrre!” at the most random intervals.

We both waited for Shenmue III to come out and finish the story. Every couple of months, she would ping me. “Hey, are they making the next Japanese Boy game yet?”

I had to give her the same answer, over and over again. “No, mom, not yet.”

My mother died on Sept. 11, 2012. One day after her birthday. She was 61 years old.

I’m not going to lie and say that I had a good relationship with my mother. There were a lot of dark times, a lot of things I’m still having to process and work through all these years later. Sometimes when I reflect on my mom, I can only see the bad. For obvious reasons.

But she was human. And humans are complex and deep. And how my mom and I bonded over Shenmue is one of those rare “perfect” memories I have of her. Even at the very end of her life, she was still talking about Shenmue. In a very strained mother-son relationship, that was one of the precious few “good times” we shared together.

When Shenmue III was announced at E3 in 2015, I was getting phone calls from people I haven’t spoken to in years. My love for all things Shenmue was so well-known that some of my friends just referred to me as “That Shenmue Guy.” You’ve no doubt seen all of the reaction videos of fan boys freaking out during the Sony announcement.

Well, my reaction was a little different. The tears came out, but they weren’t tears of joy. They were tears of regret. I immediately thought of my mom, who would never see me play though the game like she did the first two. The same way she’d never see me get my master’s degree, never see me get married or never hold a grandchild in her arms.

It should’ve been a happy moment. Yet all it did was make me feel the same pain I felt when she died. To me, Shenmue III was just another agonizing reminder that my mom wasn’t here anymore. And there wasn’t anything I could do about it.

Shenmue III came out in 2019, but I didn’t play it until last year. I knew that when I started it, those pains were going to come back.

And they did. There’s something almost Pavlovian about the “Journal music” — as soon as I hear those sad strings come in, I can’t help but get a little teary-eyed. But as I played through the game, something unexpected happen.

The pain turned into happiness. Walking around, collecting capsule toys and getting into street fights with random mooks, it sorta felt like I was 14 years old again, sitting in the living room, with my mom peering over my shoulder as I led Ryo to his destiny. Just walking around in the world of Shenmue relaxed me. It gave me this feeling — however true or untrue — that there was still some tenuous link connecting me to the past. I thought I would be sad playing the game, but I found myself laughing instead. Over and over again, I kept thinking to myself “man, Mom would’ve loved this part.”

I’m still kind of shocked by the negative fan reaction to Shenmue III. A lot of people may have disliked it, but I thought it was terrific. And it gave me an emotional soothing that I can’t recall any other game giving me in decades.

And, one day, I just thought to myself “it’s time to play Shenmue, the original, for the first time since my mom died.”

I don’t know how or why I decided the time was right. But I felt it in my bones.

Eventually, the same thing that happened when I played Shenmue III happened while I played the remastered version of Shenmue. There was an initial sorrow, but eventually that was paved over by the best kind of nostalgia — the nostalgia that reminds you that, for at least a brief point in time, everything really was alright in the world.

It took me 25 years to finally make the connection. The story of Shenmue isn’t just Ryo’s story, but in a lot of ways, my own life story. Both are stories about people who lost their parents and struggled to make sense of a confusing and sometimes predatory world. Both are stories about naive people who throw caution to the wind and embark on these long, bizarre journeys to fulfill some kind of inexplicable causa sui. The same way Ryo met a lot of interesting people and had a lot of interesting adventures on his quest to find Lan Di, I’ve experienced the same working as a journalist.

Journalist. Journal. Do I hear those strings again?

The deeper I got into my replay of Shenmue, the more I felt my mom’s spiritual presence in the background. Maybe not her actual spirit, but the imprint she left on my psyche, my character and the way I perceive the world. Shenmue might be a one-player game, but I never feel alone when playing it. Every time a Quick Time Event pops up, I swear I can feel my mom’s hand on my shoulder. “You got this, son. You always have.”

When you look at Shenmue from a storytelling perspective, it ultimately boils down to a tale of how one son processes the hurt of losing a parent. Granted, he does so in a very far-fetched and unrealistic way, but the root of the matter is unmistakable. I thought replaying Shenmue would be a traumatizing experience — but instead, it offered me relief in the strangest of ways.

I’ll have these curious little moments where I’ll just want to boot up an old save state and play Hang-On at the arcade or visit the convenience store and browse the audio cassette section or visit Tom’s hot dog stand. Sometimes, I just want to rummage through Ryo’s home, rifling through his cabinets and going through his sock drawer for no real reason at all. It took me a while to figure out what I was really doing — it was the virtual equivalent of visiting my childhood home, a place that no longer exists and hasn’t existed anywhere but in my heart for a few decades now.

There’s something special about Shenmue. When I play it, I’m not just revisiting my favorite game from my teenage years, I’m touching something unerasable from my past. There are thoughts and feelings I haven’t experienced in years that come rushing back to me when I play the game. Sometimes, I swear I can smell the kitchen of my youth when I play it or hear the pitter-patter of my mom shuffling around in the living room, probably trying to locate where she misplaced the TV remote or something. There’s some kind of ethereal bond, this invisible link to the past that still feels real and palpable when I play the game.

Every now and then Shenmue does make me cry. I guess it always will. But more often than not, it makes me smile and sometimes even laugh. At the end of the first game, as Ryo gets on that ship to Hong Kong and says farewell to the life he once knew, I get this bittersweet pang in my stomach. There’s an obvious parallel there. At a certain point, I knew I had to leave my mom behind and it obviously hurt about as much as anything has ever hurt in my entire life. But in that there’s this sense of closure that’s hard to describe. In real life, I never got to say goodbye in the right terms; as Shenmue concludes, I feel like I’m getting something of a “good ending” in my own life — this after the fact acknowledgement that there are no hard feelings and everybody is at peace, in one way or another. One chapter ends and a new journey begins.

You can be happy about that and sad about that at the same time. But there’s no bitterness or resentment or guilt. You’re not totally healed — and you know you never will be for the rest of your life — but you feel better nonetheless.

For all the endless discussions we’ve had over the years about the (purported) negative effects of video games — that they reward violence, that they cultivate addictive behaviors, that they turn young people into slack-jawed idiots, etc. — I really can’t think of another type of media that’s allowed me to process my mother’s death as deeply and beneficially as Shenmue. Not watching Ordet, not reading A Grief Observed, not listening to 2Pac’s “Dear Mama” — although all of those texts have given me some reassurance and succor over the years, no doubt.

The game evokes a certain nostalgia, but it also inspires a very different kind of hope. Shenmue allows me to look back, but it also serves as a reminder that my own story isn’t over. And nothing would make my mother happier than knowing I carried on and beat the game in her memory and honor.

Shenmue will always be something transcendent for me. It’s far more than a game, the same way your mother’s favorite recipe is more than just another dish and how your childhood home is more than just another building. Internally, it means so much more, to the point it almost becomes an element of who I am as a person.

It’s a connection — a connection to my past, a connection to a different world and most importantly a connection to my mother’s memory. And all these years later, I can still sense her presence whenever I’m playing Shenmue.

There is a very specific element of the game that’s taken on a newfound significance for me. Inside the Hazuki residence, you can find a family altar. There’s a bell Ryo can ring to memorialize his deceased parents. The game will stop for a brief cutscene and Ryo will kneel and say a silent prayer.

It’s a moment that not only sums up what makes Shenmue unique in the pantheon of video games, but the very thing that makes it mean so much to me — as a person, as a son, as a human being who will always carry scars from the past that will never truly heal.

In Shenmue, I get a feeling of comfort and redemption. An indescribable peace and acceptance kicks in, almost like my mom is telling me things are going to be OK through the ephemera of the game itself.

Hope is wherever you can find it. And that seems to be the overarching theme of the Shenmue series: it’s superficially about a teenager’s quest for “vengeance,” but what it’s really about is the pursuit of closure.

I can’t explain it. I can’t rationalize it. But I feel it. Every time I play Shenmue, it seems like I get one step closer to that spiritual resolution I’ve sought for years and years now.

And I know — somewhere in a place I can’t even begin to fathom — my mom is cheering me and “the Japanese boy” on, just like she did 20 years ago.

One reply on “Shenmue: A Grieving Son’s Story”

What a beautiful story.

I’d also like to commend you for writing a personal story like this on a personal website, for presumably personal reasons.

In a time when so much online writing is driven by attention and metrics, it’s genuinely nice to see a piece that exists just to be read, not to chase clout on “social” media.